This is a week's worth of written work done by my 12 year old daughter who is doing AmblesideOnline Year 7. Each week is a little different, depending on what else is happening, but essentially after each reading she is required to do an oral narration or some sort of written account, which could be a notebook entry, a composition or creative narration or just a retelling. I sometimes leave this up to her to decide or ask her to do something specific if I think she needs more variety.

Besides this her written work includes weekly dictation (we don't always get to this) & daily (or at least a few times a week) copywork.

Poetry

Poetry

We've been reading through the Oxford Book of Poetry as well as doing lessons from the Grammar of Poetry. This week I chose a poem, The Lady of Shalott by Tennyson, read it aloud, and had my daughter tell me its rhyme scheme (AAAABCCCB). Then I asked her to write a poem of her own following the same rhyme scheme, which she almost did:

The War of Words

Once upon a time,

Once upon a time,

In a faraway clime,

In the season of springtime,

A princess sublime,

Was held prisoner by a knight.

Many a gallant knight

Offered for her to fight

But their offers ended in flight,

And the evil knight still held the princess.

Her father did beg,

And he offered an arm and a leg,

And he did not renege,

But the evil knight was a prig,

And at the end of a year, he still held the princess.

Then one day,

The princess cried, ‘Hooray!’

For on the road, heading her way,

Came a tall knight, in silver armour.

He rode up to the door,

And kicked it on the floor,

‘Hi, evil knight,’ he said. ‘I’m here for war!’

And down he sat on a bucket of tar,

And waited for the evil knight to speak.

The evil knight drew forth his sword,

And they went out upon the sward,

‘But stop,’ said the tall knight, ‘I’m bored.

Why not have a battle of insults instead?’

In the season of springtime,

A princess sublime,

Was held prisoner by a knight.

Many a gallant knight

Offered for her to fight

But their offers ended in flight,

And the evil knight still held the princess.

Her father did beg,

And he offered an arm and a leg,

And he did not renege,

But the evil knight was a prig,

And at the end of a year, he still held the princess.

Then one day,

The princess cried, ‘Hooray!’

For on the road, heading her way,

Came a tall knight, in silver armour.

He rode up to the door,

And kicked it on the floor,

‘Hi, evil knight,’ he said. ‘I’m here for war!’

And down he sat on a bucket of tar,

And waited for the evil knight to speak.

The evil knight drew forth his sword,

And they went out upon the sward,

‘But stop,’ said the tall knight, ‘I’m bored.

Why not have a battle of insults instead?’

To be finished...she's been sick and laid up with a fever and didn't get back to it...my daughter, not the princess.

Architecture Notebook

Shakespeare and Plutarch have often provided some fruitful ideas for narrations with their rich language and drama. I used this suggestion from the Cambridge School Shakespeare as a base for my daughter's narration below:

Imagine you are Caesar's intelligence agents who have shadowed Brutus and Cassius (in Act 1, Scene 2) and bugged their converstion in order to make a report on them to their master.

She typed this one & I copied it here unedited, except for the dialogue, where I used a different colour to make it easier to read:

Imagine you are Caesar's intelligence agents who have shadowed Brutus and Cassius (in Act 1, Scene 2) and bugged their converstion in order to make a report on them to their master.

She typed this one & I copied it here unedited, except for the dialogue, where I used a different colour to make it easier to read:

Description of Brutus

Brutus is of middling height, with a stern gaze upon his countenance, and Rome in his heart.

Description of Cassius

Cassius has a lean and hungry look. He thinks too much, therefore he must forthwith be dangerous.

ACT 1, SCENE 1

Brutus and Cassius standeth together, talking in low tones, glancing this way, and that way, making certain that no one doth intrudeth forth into their conversion.

Brutus

‘How now, Cassius: what brings thee to converse with me?’

Cassius

‘Oh, my dear Brutus, ‘tis nought but friendly talk.’

There arises a shout from the populace, in the direction of Caesar’s whereabouts

Brutus

“Alack, alack, I fear me that honour hath been given Caesar. Alas for Rome! Ah me! We sinketh thus to the depths of d…. I mean, harrumph, ah, hooray!’

Cassius

‘Thou needst not fear me, Brutus, I am one of those excellent and most trustworthy people, who . . .’

Cassius’s words fade unto the air, as in the distance they heareth the voice of Caesar, who sayeth unto Antony,

‘I want fat men about me, Antonius. That Cassius hath a lean and hungry look. He thinks too much. Sniff. Such men are dangerous.’

Cassius

‘Ah, excuse me. . . now, as I was uttering, when so rudely interrupted, cough, cough, thou canst trust me, Brutus. Thou dost not approve of honours given unto Caesar?’

Brutus

‘Aye, Cassius. Methinks, thee also . . .?’

Cassius (drawing Brutus aside)

‘Oh, the day, when men fall down in front of men, made up as gods, when once they were as equals! I, fearless before foes, the terror of mine enemies, reduced to this! I, who once had to draggeth Caesar out of the Tiber!’

Brutus

‘Out upon thee! Explain thine self, eh?!’

Cassius

‘Why, my dear Brutus, upon the banks of Tiber I stood with Caesar, who turned unto me, and spake, ‘Cassius, wouldst thou jump into that flood with?’ I up and spake, ‘Aye Caesar, that would I,’ and forthwith I jumped straightway into that roaring flood, and Caesar jumped in with me. I had reached the farther bank, when whereupon Caesar cried unto me, ‘Help, o noble Cassius!’ (see what opinion he had of me!’) I turning around, with all the goodness of my heart, jumped into that flood once more, and dragged him upon the bank, for, he was too weak, forsooth, to do it himself! And now, I ask thee, Caesar holdeth the laurels?!’

Brutus (impressed)

‘Oh dear, Cassius. Of a truth, methinks thou art more fitted to hold the laurels than Caesar! I bear him no ill will, but the bettering of Rome is in my thoughts, O Cassius.'

Cassius

‘I agree, Brutus. And, moreover, when Caesar had a fever, he asked for water.’

Brutus (horrified)

‘Oh horror! What a calamity. Oh justice, thou art fled to brutish beasts, and men have lost their reason.’

Cassius

‘Yea, Brutus, I hear the trumpets this way come. Thine self I shall meet on the morrow.’

Brutus

‘Aye. Good night, good night! Parting is such sweet sorrow, that I shall say good night ‘til it be morrow.’

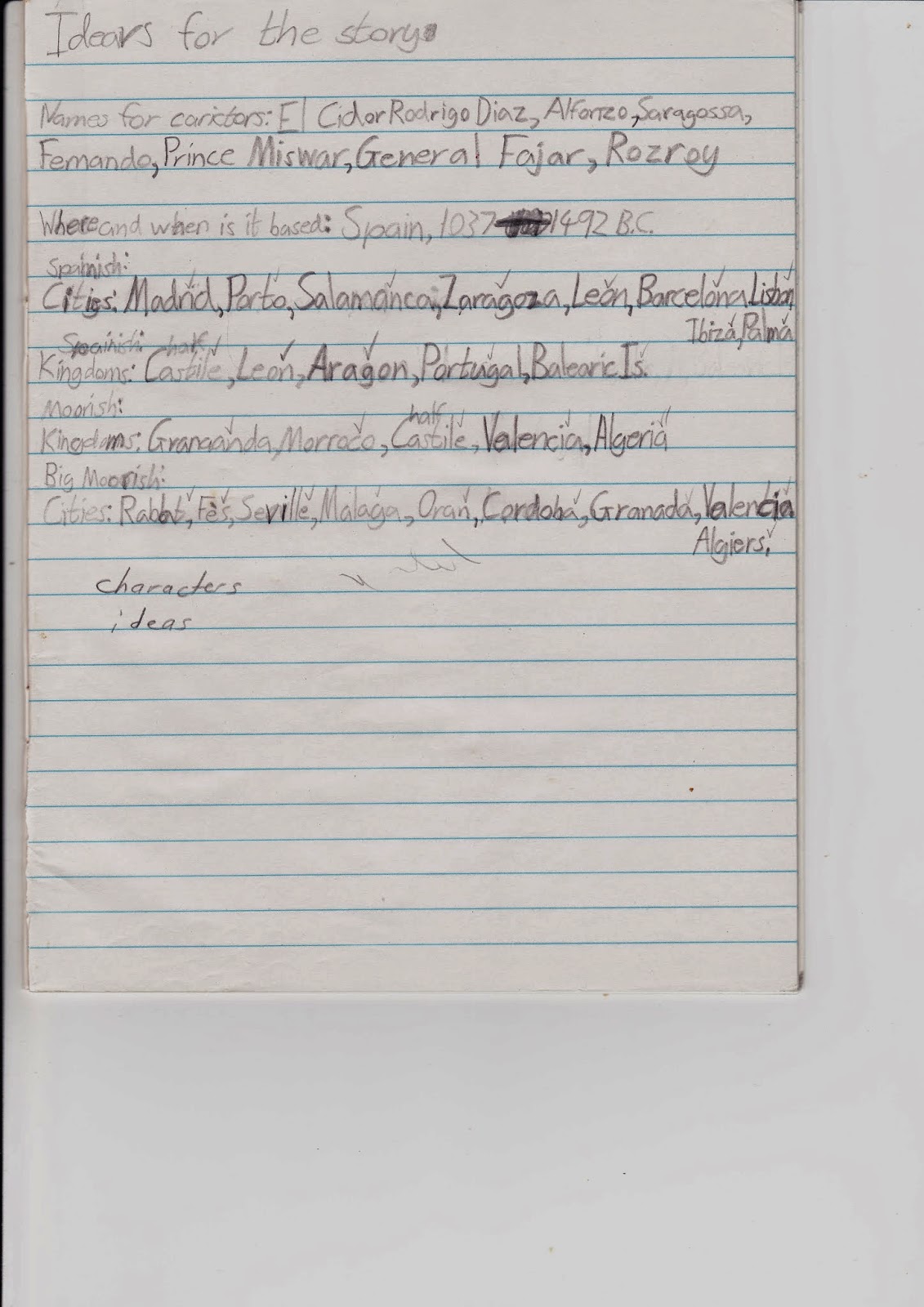

History

A handwritten narration from Churchill's Birth of Britain. She is quite neat when she does her copywork and dictation but more haphazard when doing a hand-written narration.

Science

This is from her Anatomy & Physiology book (see here & here for the books we're using for Year 7)

.JPG)