Showing posts with label Children's Classics. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Children's Classics. Show all posts

Sunday, 24 May 2020

The Lord of the Rings by J.R. Tolkien (1949)

I've just remedied the possibility that I was perhaps one of the few people on the planet who had never read (or even watched) the The Lord of the Rings (LOTR). I did read The Hobbit aloud to my daughter a few years ago and enjoyed that and it was my plan to read the LOTR some years ago after we bought a lovely boxed Folio edition but although I don't mind reading fantasy, I'm not a big enough fan of the genre to let it edge out other books I'd like to read.

The main reason I did actually start reading this about two months ago was because I knew I’d have more leisure to read an epic story with the coronavirus restrictions and also because my daughter-in-law was re-reading the trilogy and suggested we watch the movies at a later date. I always like to read a book before seeing the film version so that was the prod I needed.

I’m not even going to attempt a review of such a well-known book but I would like to share some general thoughts.

The LOTR comprises three books: The Fellowship of the Ring, The Two Towers and The Return of the King. They follow on from each other and were intended by the author to be one volume but for various reasons his publisher didn’t allow this.

Tolkien began writing LOTR soon after he’d finished writing The Hobbit and before its publication in 1937, but between his many other duties and pursuits as well as the outbreak of WWII, it wasn’t completed until 1949.

Tolkien created a whole new world with its own intricate history, peopled with diverse creatures: hobbits, elves, dwarves, wizards, orcs, trolls and men. While it was a sequel to The Hobbit, it became much more than that; it is darker, more challenging to read, and while some characters from The Hobbit re-appear and there are some similarities, LOTR is much more developed plot-wise. It is full of wisdom, mystery, humour, and many unlikely heroes.

Tolkien specifically said in the foreword to LOTR that he didn’t intend any inner meaning to the story and that he disliked allegory in all its manifestations. He preferred readers to use their own freedom of applicability (I'd interpret that as their 'moral imagination') rather than allowing the author's purpose to dominate.

Bilbo, the main character from The Hobbit, returned to his home in the Shire with a Ring in his possession. For many years he had kept this Ring safe and only his nephew, Frodo, and the wizard, Gandalf the Grey, knew about it and its power to make its wearer disappear.

One day Gandalf paid Bilbo a visit and was concerned to observe that the Ring seemed to have a strange power over his hobbit friend. Bilbo had been restless and planned to leave the Shire so Gandalf persuaded him to leave the Ring behind with Frodo when he did.

Years after Bilbo had departed, Gandalf had made a number of journeys investigating the history of the Ring, which was one of many that were forged in the distant past. During this time of Gandalf's absence, Frodo received strange tidings from dwarves and other travellers passing through the Shire and he grew increasingly restless. When Gandalf eventually returned to the Shire he was certain in the knowledge that Frodo’s Ring was The Ring of Power, the One that ruled over all others. He also brought news that the evil Lord Sauron of the Land of Mordor knew now that the Ring he presumed lost was to be found in the possession of a hobbit in the Shire.

'Three Rings for the Elven-kings under the sky,

Seven for the Dwarf-lords in their halls of stone,

Nine for Mortal Men doomed to die,

One for the Dark Lord on his dark throne

In the Land of Mordor where the Shadows lie.

One Ring to rule them all,

One Ring to find them,

One Ring to bring them all

And in the darkness bind them

In the Land of Mordor where the Shadows lie.'

Now that Frodo’s life was in danger, Gandalf urged him to leave the Shire and travel to Rivendell where the Elves dwelt. The Ring needed to be destroyed, that was understood, but Frodo did not want to be the one take it to Mordor and thought he could pass it on to another.

'I wish it need not have happened in my time,' said Frodo.

'So do I,' said Gandalf, 'and so do all who live to see such times. But that is not for them to decide. All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given us.'

Frodo did not go alone as was originally intended but was accompanied by three hobbits: Sam, Merry and Perrin. Sam was Frodo’s gardener; simple, practical, a faithful companion, the most unlikely hero, and one of my favourite characters in the story.

On their way to Rivendell they met a character by the name of Strider, a Ranger of the North, a recluse and a wanderer, who was not who he seemed to be, but who nevertheless joined them in their journey.

'All that is gold does not glitter,

Not all those who wander are lost;

the old that is strong does not wither,

Deep roots are not reached by the frost.

From the ashes a fire shall be woken,

A light from the shadows shall spring;

Renewed shall be blade that was broken;

The crownless again shall be king.'

Frodo gained Rivendell by the skin of his teeth in an unconscious state and awoke in a room with Gandalf beside him. A Council was held to decide on what should be done with the Ring and after much discussion, Frodo said, 'I will take the Ring, though I do not know the way.'

The Company of the Ring was to be nine and the remainder of the story tells of the adventures, dangers, and disappointments of this Fellowship as they fought for Middle Earth against the spreading evil that threatened to overwhelm all they knew and cared about.

One of the major themes of the book is the examination of power and its effects on those who possess it.

The Master-ring that came into Frodo’s possession had the power to consume and control its possessor. Although it extended the life of the bearer, it burdened that life, stretching and straining it. A mortal who kept one of the Great Rings did not die, but merely continued and grew wearier. If he often used the Ring to make himself invisible, he faded and eventually became permanently invisible, and in the end was devoured by the dark power.

‘But where shall I find courage?’ asked Frodo. ‘That is what I chiefly need.’

‘Courage is found in unlikely places,’ said Gildor. ‘Be of good hope!’

The themes of courage, companionship, duty and loyalty running through the book are multilayered and inspiring.

Tolkien’s linguistic genius and the complexities of plot, may be appreciated more by mature readers and such is the descriptive power of Tolkien’s writing that it is difficult to believe that his imagined world: the Shire, Mordor and Gondor, didn’t actually exist.

For me it was an ideal read during the weeks of uncertainty with the virus lockdown and restrictions. There were many challenges and disappointments for the Fellowship but hope kept resurfacing and seemingly insignificant characters played major roles and helped turn the tide in many instances.

‘There is a seed of courage hidden (often deeply, it is true) in the heart if the fattest and most timid hobbit, waiting for some final and desperate danger to make it grow. Frodo was neither fat nor very timid; indeed, though he did not know it, Bilbo (and Gandalf) had thought him the best hobbit in the Shire. He thought he had come to the end of his adventure, and a terrible end, but the thought hardened him. He found himself stiffening, as if for a final spring; he no longer felt limp like a helpless prey.’

‘Indeed in nothing is the power of the Dark Lord more clearly shown than in the estrangement that divides all those who still oppose him.’

‘...we put the thought of all that we love into all that we make.’

‘Don’t leave me behind!’ said Merry. ‘I have not been of much use yet; but I don’t want to be laid aside, like baggage to be called for when it’s all over.’

‘...it is best to love what you are fitted to love.’

'The Shadow that bred them can only mock, it cannot make: not real new things of its own.'

We watched the DVD’s over three evenings after I’d finished reading the trilogy and I annoyed everyone by saying, ‘That wasn’t in the book!’ However, I did enjoy watching them. My youngest also watched them for the first time although she’d read the books a couple of years ago and was waiting impatiently for me to hurry up and read them so we could watch together.

I think the story would be best appreciated by anyone aged 12 years and up, if they are a confident reader. It feels like it was written for around that age group in some respects but like any well written classic it has universal appeal. I don't know that I'd want to read this aloud with the plethora of names and places but it would be a great family read if you didn't mind wrapping your tongue around it all.

Graphic and detailed screen images are hard to put aside in order that your imagination may form its own, so I think it's important that the books be read before the movies. I feel that way with every book but this one more so!

Linking to Back to the Classics 2020: Adapted Classic

Saturday, 15 December 2018

Back to the Classics 2018 - Final Wrap-up

These are the books I've read this year for the Back to the Classics Challenge hosted by Karen at Books & Chocolate. I finished all 12 categories so have 3 entries in the draw.

This is my fourth year to complete this challenge and I plan to sign up again for 2019. If you are planning to do the challenge next year feel free to say hi in the comments and put a link to your post with the books you plan to read.

My original list was a little different to what I actually did but what I like about Karen's challenge is the flexibility she allows.

I don't usually have a rating system but I thought I'd try it out with these books:

19th Century Classic - The Refugees by A. Conan Doyle (8/10) Good but some of his other historically based books are better

20th Century Classic - Beau Geste by P.C. Wren (8/10) An unusual mystery in an unusual setting

Classic by a Woman Author - The Daughter of Time by Josephine Tey (9/10) I've loved everything I've read by this author

Classic in Translation - Kristin Lavransdatter by Sigrid Undset (9/10) Raw, powerful story

A Children's Classic - Linnets & Valerians by Elizabeth Goudge (7/10) Good writing but I had misgivings about some of the content

Classic Crime Story - And Then There Were None by Agatha Christie (6/10) The awful characters in this story made it hard for me to feel any connection with it. Christie was clever, but I don't always like her writing.

Classic Travel or Journey - Sick Heart River by John Buchan (8/10) Buchan is one of my favourite authors. This book is more philosophical than some of his others. It's good but I've enjoyed some of his other books more than this one.

Classic With a Single Word Title - Catriona by R.L. Stevenson (7/10) Good story but it rambles somewhat.

Classic With a Colour in the Title - Green Dolphin Country by Elizabeth Goudge (8/10)

Classic by a New-to-You Author - The Rosemary Tree by Elizabeth Goudge (7/10) Both books by Goudge were good reads. her writing is beautifully reflective.

Classic That Scares You - Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy (10/10) What more can I say than that Tolstoy was a marvellous writer?

Re-Read a Favourite Classic - Mr. Standfast by John Buchan (10/10) This was the third time I've read this book and I've appreciated it more each time I've read it.

Tuesday, 12 June 2018

Back to the Classics: Linnets & Valerians by Elizabeth Goudge (1964)

I had a mixed reaction to Linnets & Valerians, a children’s book by Elizabeth Goudge which was published in 1964. On the one hand, most of the characters in this book are attractive, well portrayed, and interesting. The storyline is involved and has plenty of appeal also but I was uncomfortable with how Goudge handled the magical side of the story as the book progressed. I think Goudge's writing is very endearing so I am genuinely sorry I can't recommend this book without reservation.

The Story

Four children, Nan, Robert, Timothy, Betsy, and their dog, Absolom, are left in the care of their grandmother when their father went off exploring in Egypt. The children were a bit too much for Grandma to handle, so she decided that Absolom must go and that Robert and Nan should be sent to boarding school while her companion, Miss Bolt (christened 'Thunderbolt' by the children) would teach Timothy and Betsy at home. The children did not want to be either educated nor separated from each other, and were determined to keep their dog. So they did what any child would want to do in that situation:

'Escape. People always escaped from prison if they could. The question was, could they? Robert was ten years old, stocky and strong, and he had a penknife, green eyes and red hair, and when a question like this presented itself to his mind he did not ask it twice.'

By coincidence, they ended up at the house of their eccentric bachelor uncle, their father’s elder brother. Although Uncle Ambrose was adamant that he did not like children, underneath he was a decent fellow. He had firm views about children and did not hold with boarding school for girls:

‘Home’s the place for girls, though they should have a classical education there. I have always maintained that women would not be the feather-headed fools they are, were they given a classical education from earliest infancy.’

He agreed to let the children stay with him subject to certain conditions:

‘I intend to impose conditions upon your sojourn with me. You will keep them or go to your Uncle Edgar, who lives in Birmingham and will dislike you even more than I do myself...

I must tell you that I have a devouring passion, not for children themselves, for I abominate children, but for educating them...’

And so began their education in Greek, Latin, and Literature, with a good amount of free time thrown in if they completed their work.

The children’s mother had died five years previously and the children were close and trusted each other. Nan, responsible, steady, and sensitive, and twelve years of age. Being the eldest, she was of a domesticated turn of mind. She 'did not have many ideas of her own because it was she who had to deal with what happened after Robert had had his.'

She also believed that ideas should be chewed on for twenty-four hours, whereas Robert was impulsive and full of ideas - especially about how to make money; Timothy and Betsy, both feisty and headstrong were aged eight and six respectively.

Although their uncle was a stern disciplinarian, he was a wonderful teacher and did genuinely love his charges. He recognised that Nan had a reflective temperament like himself so he gave her her own little parlour where she could go for privacy:

‘A parlour of her own! She had never even had a bedroom of her own, let alone a parlour...

Something inside her seemed to expand lie a flower opening and she sighed with relief. She had not know before that she liked to be alone. She sat still for ten minutes, making friends with her room, and then she got up and moved slowly around it, making friends with all it held.’

Goudge showed her knowledge of children and their needs in a sensitive, charming, and humorous manner throughout this book, but as I mentioned previously, I was uncomfortable with how she handled the magical aspects of the story. I don’t have an issue with magic per se, and our children have read Tolkien, Lewis, and other authors, some modern, whose books contain this element, not to mention fairy tales. In a fairy tale, there are consequences for evil doers, but in Linnets & Valerians there were characters with dark motives and actions who didn’t have to face the consequences of their deeds. I think this is confusing to a child.

One particular instance that bothered me was when Nan discovered a book of spells in a cupboard in her parlour. They had been written by Emma Cobley, a woman who was jealous because the man she loved married Lady Alicia. Emma used her spells to inflict Lady Alicia’s son so that he became deaf and dumb, while her husband, Squire Valerian, was afflicted with a loss of memory. Both of them were estranged from Lady Alicia for many years and she believe them to be dead. The children, with the help of old Ezra who lived with Uncle Ambrose, were able to reverse the spells and reunite Lady Alicia with her loved ones.

When Emma discovered her book of spells had been burned and her deeds revealed, she replaced the old sign of the falcon on the inn that had been removed when Squire Valerian disappeared and just went back to life as usual as though nothing had happened. No consequences.

In Tending the Heart of Virtue by Vigen Guroian, a book that explores the power of story in awakening a child’s moral imagination, he writes:

‘Children are vitally concerned with distinguishing truth from falsehood. This need to make moral distinctions is a gift, a grace, that human beings are given at the start of their lives.’

Magical realism and fantasy stories can project fantastic 'other' worlds while still paying attention to truth and without clouding real moral laws.

Guroian continues:

'Becoming a responsible human being is a path filled with potholes and visited constantly by temptations. Children need guidance and moral road maps and they benefit immensely with the example of adults who speak truthfully and act from moral strength...

some well-meaning educators and parents seem to want to drive the passion for moral clarity out of children rather than use it to the advantage of shaping their character. We want our children to be tolerant, and we sometimes seem to think that too sure sense of right and wrong only produces fanatics.'

I would have been more satisfied if Elizabeth Goudge hadn’t made Emma’s actions seem trivial.

‘She won’t do no more ‘arm,’ said Ezra. ‘’Er spells be burnt an’ she won’t do no more ‘arm. ‘Angin’ up that falcon was ‘er sign to us that she knows she’s beaten. She won’t do no more ‘arm. Glory glory alleluja!’

However, Ezra was never quite sure of the inwardness of Emma’s virtue...

Apart from this episode in dealing with Emma, the story ended well and everyone lived happily ever after.

Linking to Back to the Classics 2018: Children's Classic

Sunday, 3 December 2017

Finding Plutarch in Unexpected Places: The Forgotten Daughter by Caroline Dale Snedeker - Newbery Honor Book, 1934

The Forgotten Daughter is an outstanding book by an author who was well-known for her dedication to historical accuracy. Caroline Dale Snedeker (1871-1956) wrote numerous books for children and this book is a fine example of the research she undertook to produce an historically authentic work of fiction.

The Forgotten Daughter is a captivating story, an adventure, and a powerful tale of love, loss and forgiveness. It plunges the reader into the Ancient World; into the second century before Christ when Tiberius Gracchus was Tribune in Rome.

As I was reading this book, I felt a certain familiarity with the background historical narrative but I couldn’t remember where I’d heard it before. And then the author mentioned Plutarch. Yes! We’d read about the Gracchi and Cornelia, their mother, who devoted herself to her sons’ education:

Those she so carefully brought up, that they [became] more civil, and better conditioned, than any other Romans in their time; every man judged, that education prevailed more in them than nature.

We’ve been reading two to three selections from Plutarch’s Lives each year for the past six years, although at first I wasn’t convinced he was worth it. I wrote a post for Afterthoughts: 31 Days of Charlotte Mason relating to this and we have continued with studying the Lives because Plutarch really is worth it. Reading Snedeker's book, which was published in 1933, just made me all the more aware of how highly regarded Plutarch has been in the past.

Plutarch’s Life of Tiberius and Gaius (Caius) Gracchi is the basic material out of which The Forgotten Daughter is fashioned, and Snedeker intertwines Plutarch’s observations into her narrative to flesh out her story. This makes for a high interest story with a sense of authenticity.

The Forgotten Daughter tells a beautiful story that concerns a young girl named Chloe, the daughter of a noble Roman. Chloe’s mother and her companion, Melissa, both Greeks, had been captured by Laevinus, a Roman centurion, when their town was raided. Laevinus was so taken by Chloe’s mother that he was willing to marry her, and afterwards took her to live on a farm in the country as his wife.

Everything went well for a time, but one day Laevinus left for Rome to take some produce to market, and he didn’t return. Chloe’s mother was certain he would return and worried that he had become ill or had been involved in an accident. She was later informed that her husband had married another woman in Rome, and before long she was reduced to servitude and banished to a hovel with Melissa as her only company.

Inside the hut all the hill beauty was quenched like a candle - windowless, dim...

There, unknown to Laevinus, she gave birth to his daughter, Chloe, and not long afterwards she died, leaving Melissa to take care of the child.

Melissa and Chloe were mistreated by the supervisor of the farm and suffered a great deal.

As Chloe grew, Melissa passed on in song their Greek origins, the meeting of her mother and father, his desertion and her mother’s anguish. Chloe imbibed the atmosphere of her mother's homeland and a rich cultural heritage through these songs. This was to serve her well in time to come.

For these two there were no books or the knowledge to read them. So the sweet source of song was open to them. That source from which all books are taken, but from which no book is able to gather all the living sweetness. Melissa’s song was rude and simple, but it had that power.

Chloe grew up with a seething hatred of the father she never knew. She was beaten by the farm supervisor and lived a life of misery, and all the while Melissa strove to comfort and protect her for the sake of the friend she had loved.

In such a life there was no hope; no use to save or build up. Why they lived at all is strange. They simply awoke, worked, ate, slept, and awoke again. They were indeed the machines which the Romans thought them.

Forever besetting mankind is this temptation - to make other men into machines. Always in a new form it comes to every generation, and always as disastrous to master as to slave...

The life of a slave in the Roman Republic was keenly portrayed and Snedeker had some very insightful observations to make on Rome and Roman philosophy.

...in Roman days, after every victory, thousands of slaves were sold on the battlefield to speculators for the equivalent of eighteen cents each. They were cheap because so many of them died on the long march to Rome. So many committed suicide. So it was with slaves. But in the end Rome died itself because of them - rotted to the heart.

And this gem:

Despair in the old is a grievous thing, but not so bad as despair in the young. The young have no weapons, no remembrance of evils overcome, nor of evils endured. They have no muscle-hardness from old battles. They see only what is present, and they believe it to be forever. And they are very sure.

The Forgotten Daughter is recommended for ages 12 years to adult. I’d add, a mature 12 year old, not so much for content but Snedeker’s style is so lyrical and her comments on human frailties and philosophy are likely better suited to a young person who is thoughtful about this type of thing. But then again, the story also has action, danger, suspense and romance, which would appeal to a wide audience.

It is strange how people will try to mend their lives when the garment is torn to shreds. It is strange, too, how life’s garment, unlike human weaving, grows whole with the mending. It is as if some invisible kindness out of the air had set to work with you - here a little and there a little.

If your child has been studying Plutarch’s Lives, this is a wonderful book to further expand their pleasure in looking at the lives of the Gracchi, Crassus, Scipio, Marcus Octavius and also Ancient Rome.

The Forgotten Daughter by Caroline Dale Snedeker is my choice in Back to the Classics Challenge 2017 for an Award-winning Classic

Saturday, 25 November 2017

AusReading Month: Seven Little Australians by Ethel Turner (1894)

Seven Little Australians by Ethel Turner is a beloved Australian children’s classic that was first published in 1894 and has never been out of print since. So it with some trepidation and ducking of the head that I am going to say that I was fairly underwhelmed when I finally got around to reading it. My three girls read it before me - they were about 9 years of age when they first read it. As far as I remember, they all liked it, although it didn’t appeal to them as much as some of the other Australian classics they read around the same age e.g. The Silver Brumby and Billabong books.

At one point the story reminded me of an incident in Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women, which was published twenty-five years earlier. Meg is the eldest daughter of the family in this book, as was Meg (Margaret) in Little Women. In both books ‘Meg’ is influenced by another girl to put on airs and act out of character and a young man is pivotal in both instances in helping 'Meg' see the foolishness of her behaviour.

My 12 year old re-read Seven Little Australians recently so I asked her if it reminded her of any other book she’d read. It hadn’t, and I mentioned that I thought in one part that it was similar to Little Women. Her reply was that ‘Seven Little Australians didn’t carry on about morals, unlike Little Women...'

But my daughter also said that she hated the ending.

Which brings me to a couple of things I think was problematic with the story: the ending felt rushed and melodramatic, and the characters were never satisfyingly developed. I never felt I got to know anyone well enough and out of the two characters I thought had development potential, one is dispatched by the author before the story finishes.

However, the book is definitely worth reading and the writing itself is excellent and of literary quality, as you would expect of a classic that has never been out of print.

Linking up for the AusReading Challenge 2017 @ Brona's Books

At one point the story reminded me of an incident in Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women, which was published twenty-five years earlier. Meg is the eldest daughter of the family in this book, as was Meg (Margaret) in Little Women. In both books ‘Meg’ is influenced by another girl to put on airs and act out of character and a young man is pivotal in both instances in helping 'Meg' see the foolishness of her behaviour.

My 12 year old re-read Seven Little Australians recently so I asked her if it reminded her of any other book she’d read. It hadn’t, and I mentioned that I thought in one part that it was similar to Little Women. Her reply was that ‘Seven Little Australians didn’t carry on about morals, unlike Little Women...'

If you imagine you are going to

read of model children, with perhaps a naughtily inclined one to point a

moral, you had better lay down the book immediately...

Not one of the seven is really good, for the very excellent reason that Australian children never are.

Not one of the seven is really good, for the very excellent reason that Australian children never are.

But my daughter also said that she hated the ending.

Which brings me to a couple of things I think was problematic with the story: the ending felt rushed and melodramatic, and the characters were never satisfyingly developed. I never felt I got to know anyone well enough and out of the two characters I thought had development potential, one is dispatched by the author before the story finishes.

However, the book is definitely worth reading and the writing itself is excellent and of literary quality, as you would expect of a classic that has never been out of print.

Linking up for the AusReading Challenge 2017 @ Brona's Books

Friday, 28 April 2017

Devil's Hill by Nan Chauncy (1900-1970)

Devil's Hill by Nan Chauncy was published in 1958 by Oxford University Press and is a sequel to Tiger in the Bush but may be read as a stand alone book.

Eleven year old Badge Lorenny lives with his family in a secluded valley close to the Gordon River in Tasmania. The dreaded day comes when he has to leave his home to go to live at his Uncle's farm and attend school for the very first time. He doesn't like his cousin Sam who made him feel like a fool when they'd met a couple of times previously, and he doesn't want to leave the home he knows and loves.

Badge and his Dad head off through the dense Tasmanian forest and reach the banks of the Gordon to find it a raging torrent after recent storms. 'The Wire' his Dad built was still intact - a spider web of a structure dangling above the torrent below. They crossed over, sliding with their feet side ways on the lower wire while holding on to the upper wire with their hands.

On the other side, Badge's Uncle Link was there to meet them with the news that school was closed due to an outbreak of whooping cough. Arrangements were made for Sam to come to stay with Badge and his family at the next full moon, but when the time came there were a couple of unexpected extras - Sam's two younger sisters Bron and Sheppie, had to tag along with him, much to his disgust, as their mother had been admitted to hospital and the girls couldn't be left at home on their own.

It seemed like Sam's visit was going to be a disappointing failure until the tracks of a missing calf were found and Dad decided to take everyone on an expedition to go in search of it.

Unexplored bushland, encounters with snakes, and finding a hidden cavern are part of their adventures but the expedition also proved to be an opportunity for Bron's starved soul to be filled and for the development of true friendship between Badge and Sam.

The nights were fine and clear, filled with still beauty and the occasional weird cry of owls wailing for 'More-pork! More-pork!' - and once the snarling cough of a Tasmanian devil hunting far away in the hills.

Each night after the evening meal Badge slipped outside to study the moon, for the Lorennys had no calendar with dates he could cross out with a pencil. The old moon lost shape like ice thawing in the bottom of of a bucket, and soon bedtime came before it rose at all.

Chauncy has written an engaging and lively story for children around the ages of eight or nine years and up. Badge took after his mother' 'Liddle-ma' in temperament and I liked the way Chauncy pictured their relationship. Ma understood her son's quiet and shy nature and loved him deeply without coddling him, whereas Sam's mother was overindulgent and was said to fuss over her son too much with the result was that he was sulky and spoilt when things didn't go his way.

All Nan Chauncy's children's books are set in Tasmania and reflect the love she had of the outdoor life, her knowledge of nature, and her own childhood spent in the bush. Her writing was innovative for the time and introduced a new realism - 'the adventure of everyday living and ordinary lives' - into children's literature when many other authors were more idealistic and superficial. In Books in the Life of a Child, Maurice Saxby said that while other authors were describing 'travel-brochure' pictures of Australia, Nan Chauncy, 'began to write of the Tasmania that she knew intimately and about which she felt passionately.'

She wrote, 'not of the wide open spaces, or of cities, but of what she had experienced...and to this she gave imaginative life.'

'Nan Chauncy was one of the first of a wave of writers who were to give Australian children's literature a worldwide reputation for quality.'

Devil's Hill won the Children's Book of the Year Award in 1959.

More information on the author:

Chauncy Vale in Tasmania

An Edwardian Adventure & Success Story

Mercury Newspaper article

A short biography

Except for this title published by Text Publishing, Nan Chauncy's books are, unfortunately, out of print.

Monday, 3 April 2017

Classic Children's Literature Event 2017: My Friend Flicka by Mary O'Hara (1941)

My Friend Flicka by Mary O'Hara has sat unread on our bookshelf for nearly twelve years since I first found it in a secondhand book store and recognised the title as being a Children's Classic, but not knowing much else about it. I decided to read it for the Children's Classic Literature Event this year as my 12 year old daughter loves horses and I thought I'd see if it was suitable for her.

I wasn't a horse fanatic when I was a child, but there's enough to enjoy in this book regardless of whether you like horses or not. The main thread of the narrative is the love a boy has for a filly (Flicka) and how that love is returned, but it's also a tender portrayal of family relationships - a stern ex-army father, a sensitive mother, and their two sons, Howard and Ken - and this added theme broadens its appeal even more.

Ken is a dreamy, scatterbrained, and irresponsible ten year old and his father just doesn't understand him at all. Ken always manages to get on the wrong side of his father while his older brother, Howard, is more like his Dad and has an easier time relating to him.

Ken felt as if he had been put out of the ranch, out of all the concerns that Howard was in on. And out of his father's heart - that was the worst. What he was always hoping for was to be friends with his father, and now this...His despair made him feel weak.

Ken desperately wants his father's approval and friendship but everything he does seems to drive them further apart. When Ken fails to be promoted to the next grade by his teacher his father is furious, but the only thing that will motivate Ken is having a colt of his own. And this his mother understands.

The story takes place in Wyoming in the USA and the author's vivid writing creates such a tangible sense of the countryside that it's easy for someone like myself, in a completely different part of the world, to imagine the setting. She also succeeds in depicting the various characters in a convincing manner - the four members of the McLaughlin family, the ranch workers, the horses and their individual characteristics, the itinerant family trying to eek out an existence - each are realistic and are heart-renderingly fleshed out by her descriptive powers.

I'm surprised that this book doesn't seem to be that well-known (well, in Australia at least) except for those who read it as a child themselves. It was made into a movie but a female character was substituted in Ken's place and from what I've read it didn't do the book justice. It certainly deserves its place amongst children's classics for its beautifully crafted writing and for the way the author portrays conflict in family life.

I think this book would be best suited for an independent reader of about 13 or 14 years and up, even though the main protagonist is 10 years old. Rob McLaughlin is a just man but has a quick temper, a rough tongue, and a harsh manner. "Damn it !" and sometimes "God damn it!" are part of his regular vocabulary and there is some tension between himself and his wife, Nell, that would better suit an older child. However, I think it would work well as a read aloud with a younger child with a little editing in places as there are some great themes worth exploring.

Some favourite bits:

"The most affectionate animal in the world," said Rob. "You don't see the young ones leaving their mothers if they can help it. They stay in the family group. You'll often see a mare on the plains with a four-year-old colt, and a three-year-old, and a two, and a one, and a foal. All together. They don't break up unless something happens to make them. And they never forget."

"They learn from their mothers. They copy. They do everything their mothers do. That's why it's practically impossible to raise a good-tempered colt from a bad-tempered mate. That's why I never have any luck with the colts of the wild mares I get. The colts are corrupted from birth - just as wild as their mothers. You can't train it out of them."

McLaughlin never allowed anyone to show, or even to feel, any grief about the death of the animals. It was an unwritten law to take death as the animals take it, all in the day's work, something natural and not too important; forget it. Close as they were to the animals, making such friends of them, if they let themselves mourn them, there would be too much mourning. Death was all around them - they did not shed tears.

"...I maintain that it's not insane for a freedom-loving individual man or beast, to refuse to be subdued."

"My experience has been that the high-strung individual, the nervous, keyed-up type - is apt to be a fine performer. It's the solitary, or the queer fellow, that I'm afraid of. Show me a man who plays a lone hand - no natural gregariousness, you know - the lone wolf type - and I'll show you the one who's apt to be screwy."

"Flicka has been frightened. Only one thing will ever thoroughly overcome that, and that is, if she comes to trust you. Even so, some bad reactions of the fear may remain. This does not mean that you must not master her. You must. She will have many impulses that must be denied because you forbid the actions that rise from them..."

Mary O'Hara continues her animal saga in the following two books:

Thunderhead

Green Grass of Wyoming

Some information on the author is here.

Linking to Simpler Pastimes for this month's Classic Children's Literature Event. Check it out for some wonderful literature!

Wednesday, 22 March 2017

Classic Children's Literature Event

This event is in its fifth year and this is the third year I've participated in it. It's only a month long and there is also an optional read along - Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. See Simpler Pastimes for more information.

This year I'm planning to read these books:

My Friend Flicka by Mary O'Hara (1941)

Devil's Hill by Nan Chauncy (1958)

And if time permits, maybe one or two others.

Wednesday, 1 June 2016

Ambleside Online Year 5 - Reading Kim by Rudyard Kipling

Kim is scheduled for Literature in Term 3 of Ambleside Online Year 5. I started listing vocabulary that I thought may need some explanation and research but then I came across this very helpful chapter by chapter resource at the Kipling Society website. I think it covers just about everything that could possibly be problematic, plus some!

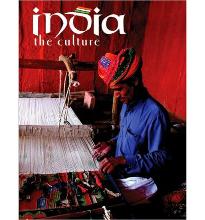

To get some background on India culturally and historically, I got together the following maps, websites, books and images that I thought were (or could be) helpful:

For a general background on India, these books by Bobbie Kalman are well done:

'The major world religions and their beliefs about God. Hinduism, Buddhism, Islam, Christianity, and New Age...'

Fairly simple explanation of various religious beliefs with a little graphic to describe each one. I read through some of this with Moozle prior to her starting Kim.

The notes on the Kipling Society web pages I linked to above define the various religious beliefs/cultures as they come up in the story, but I liked the graphics at this website which helped explain things more clearly.

Kim was published in 1901 and the setting was India under British rule. In 1947, Colonial India was divided into two separate states: India and Pakistan (the Partition of India). The map below shows India prior to Partition.

There is some history here and maps to show the changes which occurred as a result of Partition.

Zam-Zammah, Kim's gun.

He sat, in defiance of municipal orders, astride the gun Zam Zammah on her brick platform opposite the old Ajaib–Gher — the Wonder House, as the natives call the Lahore Museum.

(Kim: Ch 1)

The Grand Trunk Road - map and photos

‘Look! Brahmins and chumars, bankers and tinkers, barbers and bunnias, pilgrims and potters — all the world going and coming. It is to me as a river from which I am withdrawn like a log after a flood.’

And truly the Grand Trunk Road is a wonderful spectacle. It runs straight, bearing without crowding India’s traffic for fifteen hundred miles — such a river of life as nowhere else exists in the world.

(Kim, Chapter 3)

'The Great Game' - the struggle between the British and Russian Empires for supremacy in Central Asia. In Chapter 3 of Susan Wise Bauer's Story of the World, Volume 4, she writes about Russia and Britain's attempts to try to gain control of Afghanistan. This chapter is scheduled in Week 26 of Ambleside Online Year 5.

More on The Great Game here (for children) and here.

Benares, now known as Varanasi (Kashi); Ganges River. Some great photos here

Indian Himalayas

Simla (Shimla) c.1900 the capital city of Himachal Pradesh, and the summer capital of the British-Indian Empire.

The Spiti Valley is a desert mountain valley located high in the Himalayan Mountains in the north-eastern part of the Indian state of Himachal Pradesh. The name "Spiti" means "The Middle Land", i.e. the land between Tibet and India.

Sepoys - Indian soldiers under the command of the British

Wednesday, 27 April 2016

Golden Fiddles by Mary Grant Bruce (1928) Classic Children's Literature Event

Mary Grant Bruce is mostly known as the author of the Billabong books but she also wrote a number of other books. Golden Fiddles is one of these and is a stand alone book that tells the story of the Balfour family - Mr and Mrs Balfour and their four children, Kitty, Norman, Elsa and Bob - who are trying to eek out an existence on a farm in Tupurra, a fictitious town in country Victoria. Although the family barely makes ends meet, they live happily enough, although Mr. Balfour is taciturn and pre-occupied with their lack of finances. His attitude creates resentment in his older children and as the story begins we see this tension playing out in the family.

'I wouldn't mind being poor,' (Kitty) said. 'There aren't any rich people about here. But I'd like to be poor cheerfully - not to fuss and worry all the time, as Father does, and always making the worst of things. Why, he looks as if the world were coming to an end when any of us want new boots, till it makes one ashamed of having feet!'

...Father's hard to work for, Mother. A bit of praise doesn't cost anything, but he doesn't give that either. I suppose he has got so used to being economical that it affects his tongue! Norman won't stand it for ever, you know: when he gets a bit older he'll go away, and then Father will find out that he has lost a jolly good helper.

Kitty talks to her mother about leaving home eventually to become a chef...

'I want money, and I'm going to get it with the only talent I've got.'

'Money isn't everything, Kitty.'

'Well, Father has brought us up to think it is. And it does make the wheels go round, Mother. I want to be independent, and I want to see something beyond a hill farm in Gippsland...'

The family looked forward to one day in the year which loomed above all others: 'Show Day.' The whole family gloried in the occasion and entered the various competitions. This year each of the Balfour children won prizes in the different events. Bob was overjoyed when his pony won first prize in the ring and once at home he talked excitedly about entering the jumping event in next year's show.

Mr Balfour, however, dropped a bombshell by announcing he had sold Bob's beloved pony. Jim Craig had offered to buy the pony for more than it was worth after seeing him perform at the Show. It was an offer too good to refuse. Now Bob had to watch someone else ride his pony to school and put up with the chaffing and ridicule from his schoolmates as he rode double behind Elsa on her old nag.

He knew what he had to face at school; that ordeal could not be dodged. But no one watched him leave home, except his father; and Walter Balfour, seeing, from his work in the paddocks, the sad little trio go down the track, bit hard on his pipe stem and muttered curses on ill-luck and poverty. The thought of Jim Craig's cheque burned in his soul. He was by nature neither cruel nor hard, and he loved his children and was proud of them. But care and worry had made a crust over his heart.

A week of misery followed for everyone. Bob was sullen and had three fights at school resulting in a magnificent black eye. Norman didn't whistle as he went off to milk the cows. Mealtimes were unusually quiet and tense.

One hot evening they sat on the veranda after tea. Mrs Balfour opened a letter that had come earlier in the day and as she read, she grew white and began to tremble.

Her Scrooge of an uncle had died and left her eighty thousand pounds!

What follows is hinted at in this selection of chapter titles: The Recklessness of the Balfours; The Horizon Widens; The Golden Fiddles Play; The Growth of the Balfours; The Waking of Kitty; Realities and The New House of Balfour.

Through numerous circumstances and mishaps, the family learns that money doesn't buy happiness; that they all need some sort of work, not the gruelling type they had before, but something worthwhile that they can put their hands to. They also learn to appreciate each other as a family and to understand their father.

They talked of Tupurra and the old days. Time had drawn a veil over the hardships and the dullness of that long-ago life; looking back they seemed to remember many good things.

'All the same, it was a hard life,' Kitty said, at length. 'And yet, we were pretty happy, even if we used to grumble because we were so poor. The queer thing is that I believe we were happier then than we are now, when we've got everything we ever longed for. But that's ridiculous if course.'

'I don't know,' Elsa said slowly. 'Some things were better then. For one thing, I don't remember more than about three times that we ever quarrelled.'

Golden Fiddles is an enjoyable story with just the right level of realism for a reader of around 11 years of age and up. As it was written in 1928, the word N***er is used in places. In this story it's the name of Bob's pony, so it crops up quite a bit whenever the horse in mentioned. The only other occurrence is in a comment Elsa makes: 'Father works like a n***er in the garden...'

I wrote some thoughts on literature and its associated language when I talked about the Billabong series by the same author. I think C.S. Lewis's words below are helpful in this situation, and although a book written in 1928 is not old in the sense that Lewis was speaking about, it does reflect a way of thinking or an outlook which is quite different from the present.

Every age has its own outlook. It is specially good at seeing certain truths and specially liable to make certain mistakes. We all, therefore, need the books that will correct the characteristic mistakes of our own period. And that means the old books. All contemporary writers share to some extent the contemporary outlook - even those, like myself, who seem most opposed to it.

Authors such as Mary Grant Bruce (1878-1958) lived through the class conflict of the 1880's in Australia and the great worker's strikes, the First World War, and the lead up to the Great Depression, before she wrote Golden Fiddles. I couldn't begin to imagine what she lived through - incredible change, loss and upheaval but I am willing to overlook her mistakes in order to benefit from her truths. The discomfort that these older books sometimes generate opens our eyes and minds. Some of our best discussions at home have come via the avenue of literature when we've been faced with these uncomfortable ideas and attitudes. As I've often mentioned when writing about books, I often edit as I read aloud, depending on the child's age and/or maturity, or use the opportunity to discuss attitudes etc. when appropriate. It's easier for me to do this now than it was years ago as I've learnt the importance of preparing my children for a world that's often uncomfortable.

Linking this to Simple Pastimes as part of the Classic Children's Literature Event 2016.

PS. The book was made into a mini-series in 1991 but I haven't seen it.

Monday, 18 April 2016

A Little Bush Maid by Mary Grant Bruce (1875-1958) - Classic Children's Literature Event 2016

A Little Bush Maid was published in 1910 and is the first book in the Billabong series by Mary Grant Bruce. There are fifteen books altogether and they follow Norah Linton from when she was a twelve year old growing up at Billabong, her father's property in rural Victoria, through to her adult years.

It's best to read the books in chronological order just to get the characters straight (although we didn't because it took us a decade to gather all the titles in the series) but the books do stand alone.

The author wrote the Billabong series over the years 1910 to 1942 and they reveal a very different Australia than that of today. They are historically interesting - three of them have World War I as a backdrop (From Billabong to London; Jim & Wally; Captain Jim) and are set in locations other than Australia.

A Little Bush Maid starts off slowly as Norah and the other characters are introduced. Norah's father was widowed when she was a baby, and he was left to bring up both her and her beloved older brother, Jim. Her upbringing so far has been unconventional. She has had no formal schooling and she spends her days in her father's company, helping out on the property and growing 'just as the bush wild flowers grow.' Jim is at boarding school in Melbourne and as the story opens, he comes home with two of his friends, Wally and Harry, for the school holidays.

A Little Bush Maid may not immediately entice a young reader as they may initially be put off by the lack of action, but it is worthwhile to keep going. There is still a good deal of lighthearted, humorous banter between the characters and when the action does begin, the story picks up quickly. Norah discovers the camp of a mysterious old hermit, the young people have encounters with venomous snakes, a disgruntled swaggie sets fire to the Linton property and a visit to the circus nearly ends in tragedy.

The title of the first book probably isn't appealing to boys, but although Norah is the main character, there are strong male characters in all the books.

Age-wise, a confident reader of nine would enjoy this book, but if they like the book as much as some of my children did, you will want to start looking for more books in the series. They are out of print but the first title can generally be found easily enough and a kindle version is available online at Gutenberg (see below).

The Mary Grant Bruce Official Website has a list of the books in chronological order.

As the book was written in 1910, the attitudes and views reflect that time period. Chinese workers, Aboriginals and servants have attributes ascribed to them that are not acceptable these days and in 1992 a revised edition produced by Angus & Robertson was published with some omissions to reflect this.

1992 Version

We have an unabridged copy and a 1992 edition and I noted some of these changes:

Norah was driving a horse and carriage and referred to the two horses as 'Darkie' and N***er. In the revised edition the second horse's name was changed to 'Blackie.'

A remark made about black Billy, the Aboriginal station hand was omitted:

"Queer chap, that," said Dr Anderson, lighting a cigarette. "That's about the only remark he's made all day."

I'm surprised they didn't omit the reference to the cigarette...

This sentence referring to the Chinese gardener was omitted:

Wally's own idea was to tie him up by the pigtail, but this Jim was prudent enough to forbid.

In the afterward written by Barbara Ker Wilson in the 1992 revised edition she states:

With hindsight, we disclaim many of the ideas, opinions and attitudes of 1910, and a few paragraphs which might be thought of as racist today have been omitted from the text. But it would be profitless to criticise the author of a story written at that time for relaying the attitudes of her day through her characters.

Another revised edition (illustrated, same text as the book above & easy to find)

Interesting - we've been listening to an audio version of Tom Sawyer by Mark Twain and I was thinking how that book would be absolutely decimated if you took out the ideas, opinions and attitudes of the time in which it was written.

Literature is the product of a culture. Alexandr Solzhenitsyn said that 'literature is the living memory of a nation.' If we sanitise our past we are removing those memories and how do we learn and overcome our blind spots if we do not remember?

Gutenberg has four books in the series available in a kindle edition:

1) A Little Bush Maid

2) Mates at Billabong

6) Captain Jim

7) Back to Billabong

This hardback version is unabridged and was published by John Ferguson Pty Limited in 1981. It also contains the next book in the series, Mates at Billabong:

An unabridged audio published by Bolinda Publishing is also available. I haven't listened to it but there's an excerpt here.

We used The Little Bush Maid as a substitute for American Tall Tails in AO Year 3. The Billabong books fit chronologically into Years 5 & 6 of Ambleside Online but we've mostly used them as free reads from the age of around 9 years.

Linking this to the 2016 Children's Classic Literature Event at Simpler Pastimes.

Tuesday, 5 April 2016

2016 Classic Children's Literature Event: Sir Nigel by Arthur Conan Doyle

During the month of April I'm linking up at Simpler Pastimes for Amanda's Classic Children's Literature Event. I hope to read at least two books for the Event and here is the first (I cheated and actually started before the 1st April...): Sir Nigel by Arthur Conan Doyle.

Sir

Arthur Conan Doyle is best known for his Sherlock Holmes' detective character

but he also wrote some excellent historical novels.

In

1891, Doyle's novel, The White Company, was published. This book tells of the

adventures of Sir Nigel Loring and his men and is set during The Hundred Years'

War. Fifteen years later, in 1906, the 'prequel,' Sir Nigel, was published. This

book, set at the beginning of the war, details the exploits of the squire

before he became a knight.

Nigel

of Tilford is the last in a long line of a famous but now impoverished family.

Brought up by his aged grandmother, the Lady Ermyntrude, Nigel is small in stature but has a heart

full of chivalrous intent, and is determined to win honour and become a

knight.

Together

with his lusty attendant, Aylward, they find adventure and seek their fortunes

in England and France alongside Edward III, the Black Prince and Sir John

Chandos, a Knight of the Garter.

If

you've read The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood and Otto of the Silver Hand by Howard Pyle, you will get an idea of what

to expect from this book. Doyle's humour is reminiscent of Pyle's Robin Hood.

Sir Nigel is brimming with humorous episodes and downright fun as Nigel follows

his romantic ideals and goes about 'winning worshipful worship.' However, there

is also much serious content and brutality that reflects the time period of the

story, which is also the case in parts of Otto of the Silver Hand, but even

more so in Sir Nigel.

A

couple of instances of the more serious aspects of the book which come to

mind:

In

Chapter XI of the story, the reader is introduced to Sir John Buttesthorn and his two daughters, Edith and Mary:

...Never

had two more different branches sprung from the same trunk. Both were tall and

of a queenly graceful figure. But there all resemblance began and ended.

Edith

was yellow as the ripe corn, blue-eyed, winning, mischievous, with a chattering

tongue, a merry laugh, and a smile which a dozen of young gallants, Nigel of

Tilford at their head, could share equally among them. Like a young kitten she

played with all the things that she found in life, and some there were who

thought that already the claws could be felt amid the patting of her velvet

touch.

Mary

was as dark as night, grave-featured, plain-visaged, with steady brown eyes

looking bravely at the world from under a strong black arch of brows. None

could call her beautiful, and when her fair sister cast her arm around her and

placed her cheek against hers, as was her wont when company was there, the

fairness of the one and the plainness of the other leaped visibly to the eyes

of all, each the clearer for that hard contrast. And yet, here and there, there

was one who, looking at her strange, strong face, and at the passing gleams far

down in her dark eyes, felt that this silent woman, with her proud bearing and

her queenly grace, had in her something of strength, of reserve, and of mystery

which was more to them than all the dainty glitter of her sister.

Later

on in Chapter XII, Edith is deceived by a cunning nobleman into running away

with him after he makes a false promise of marriage. Nigel, Mary and an old

priest seek out the couple and find, as they expected, that the nobleman had no

intention of marrying Edith but it was not until Nigel had a dagger at the

man's throat that Edith saw through the deception. She returned home chastened and

thankful that she had escaped from a situation that would have brought shame

and disgrace to both herself and her family.

This

situation was handled so well by Doyle that younger readers could get a sense

of the moral peril Edith was in without being burdened by information above

their heads or maturity level.

Some

other scenes occurred which may be too intense for some younger readers:

The

butcher of La Brohiniere had captured some of Nigel's company and imprisoned

them in a castle and when the English tried to make an attempt to free them, La

Brohiniere started to hang some of the men from the parapets. When Nigel later

succeeded in finding a way into the place where the English were imprisoned, he

found a strange and horrible scene:

It

was a great vaulted chamber, brightly lit by many torches. At the farther end

roared a great fire. In front of it three naked men were chained to posts in

such a way that, flinch as they might, they could never get beyond the range of

its scorching heat. Yet they were so far from it that no actual burn could be

afflicted if they could but keep turning and shifting so as continually to

present some fresh portion of their flesh to the flames. Hence they danced and

whirled in front of the fire, tossing ceaselessly this way and that within the

compass of their chains, wearied to death, their protruding tongues cracked and

blackened with thirst, but unable for one instant to rest from their writings

and contortions.

Sir

Nigel would appeal to anyone interested in historical, well-paced, adventurous

types of book. I'd recommend it for confident readers who have enjoyed books by

authors such as G.A Henty, Rosemary

Sutcliff, Henry Treece, and especially Howard Pyle. Each of these

authors wrote realistic historical fiction for children. Most of my children

read this book around the ages of 10 to 12 years and thought it was a great

story. Moozle (11years of age) is reading it for the second time. I think the

humour throughout is an added attraction for her and helps to keep the story

buoyant.

The passages you may want to

pre-read before handing the book to your children are from these two chapters

which I've linked to a free online version:

Ch XII How Nigel Fought the

Twisted Man of Shalford

Ch XX How the English

Attempted the Castle of La Brohiniere

There

is an excellent audio version narrated by Stephen Thorne:

Arthur

Conan Doyle was proud of the research that went into his historical novels and

he wrote this explanation about the content of Sir Nigel:

I am aware that there are

incidents which may strike the modern reader as brutal and repellent. It is

useless, however, to draw the Twentieth Century and label it the Fourteenth. It

was a sterner age, and men’s code of morality, especially in matters of

cruelty, was very different. There is no incident in the text for which very

good warrant may not be given. The fantastic graces of Chivalry lay upon the

surface of life, but beneath it was a half-savage population, fierce and

animal, with little ruth or mercy. It was a raw, rude England, full of

elemental passions, and redeemed only by elemental virtues. Such I have tried to

draw it.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)