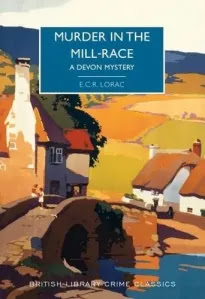

I’ve been slowly collecting books published by the British Library Crime Classics. I judged these books by their covers when I came across my first one and haven’t been disappointed in those that I’ve read so far. John Bude and E.C.R. Lorac are the authors I’ve mostly read.

Murder in the Mill-Race by E.C.R. Lorac (1952) – like other books I’ve read by this author, it has an intriguing plot and is written in a literary style. When a murder occurs in a village in Devon, the residents are determined not to allow strangers to know their secrets and Chief Inspector Macdonald is hampered in his investigations. Macdonald is a very likeable cop with a great sense of humour and an ability to show compassion at the right time. Lorac was an important and influential Golden Age author and was particularly skilled in her descriptions of place and atmosphere. Some of her books, including this one, have a rural setting while others like the one below are set in London.

These Names Make Clues by E.C.R. Lorac – this story was first published in 1937 but languished in obscurity for more than eighty years until it was published by the British Library Crime Classics in 2021. It has the feel of the more traditional Golden Age crime novel with a locked room scenario.

Macdonald was invited to a Treasure Hunt party hosted by Graham Coombe and his sister, Susan. The attendees included detectives – in literary, psychological and practical fields of work who had never met each other. They were each given a pseudonym (Jane Austen, Laurence Sterne, Fanny Burney, Samuel Pepys…) and clues of a literary, historical and practical nature and instructions on where to find their next clue. And so the guests began their hunt, wandering through the house. About an hour into the party, the electricity suddenly went out. When it was eventually restored it was noticed that one of the guests was missing. The missing person was found dead of a suspected heart attack.

''The evening began as a farce and has ended in a tragedy.

It was an essential of detection to regard every contact in a case as dispassionately as the symbol of an equation; the likes and dislikes of a detective had to be kept apart from the reasoning mental processes whereby he assessed probabilities. With one side of his mind, Macdonald liked Graham Coombe and his sister. They were a friendly and amusing pair, whose qualities, imaginative and whimsical in the former, practical and sensible in the latter, made a good foil to one another.

With the other side of his mind, Macdonald had to consider how either – or both – would fit as culprits in this evening’s work.''

I’ve been reading Anne Perry’s William Monk series over the past few months. In a few of the books I’ve read the murderers actions seemed to be almost justified because of the dreadful situation they were in. In These Names Make Clues a similar situation occurs but Macdonald’s response was,

''From some acts there is no escape…If you take another person’s life, for no matter what reason of private anger or vengeance, your own is surely forfeit. You may escape punishment by the law, but your own awareness you never escape…murder never can be judged as a good method of righting other wrongs. I believe that,'' he added very simply and earnestly, ''otherwise my job would be an intolerable one.''